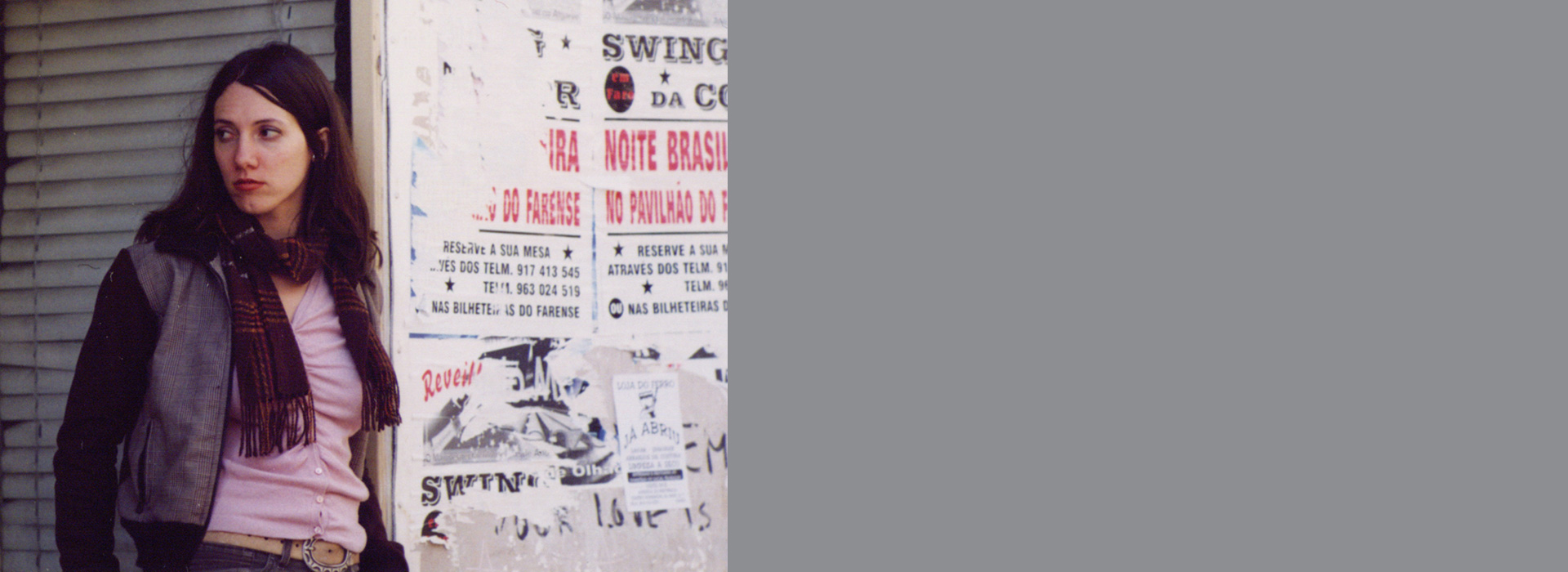

A PORTRAIT OF DIRECTOR ZISKA RIEMANN

photo courtesy of Ziska RiemannSitting in a cosy corner café in Berlin’s formerly upcoming but now definitely arrived Schöneberg district, Ziska Riemann is rocking a dark blue and black, wooly, but definitely not spiky, certainly elegant and fluffy ensemble. It took a little back and forth to nail the now official description of her outfit but with that settled, it’s on to other things: the great coffee, the lovely smell of cheese and why the place won’t serve certain snacks at certain times. “They’re French,” Riemann says, “so they have very strict rules!” Makes perfect sense when she puts it like that.

And that’s the thing for Riemann, the importance of framing and defining the terminology, language and images for the audience. But given her extensive background as a comic book author and artist it is also no surprise: after all, the woman creates visuals.

“Film people understand graphic novels,” Riemann explains. “You can call them graphic novels, but for me they are more of an illustrated novel. But whatever you call them, they are filmic tales,” she continues, “and I work the same way with a camera: which is the right angle? Shall we zoom or track in? Pan left or right? It all made for great film training.” At which point, take note, Riemann did not attend film school and is not only none the worst for it, she’s most likely all the better! She did study Fine Arts, however, “not long enough to get the diploma! But I grew up with Jim Jarmusch, David Lynch arthouse films and pop culture; videos, music clips, horror films etc.”

“I first started to express myself artistically in visual terms but I have always been a storyteller,” Riemann says. “I wrote short stories as a kid instead of keeping a diary. It gave me anonymity and thus more freedom, and later, when I realized I could combine it with drawing, I started doing the same for graphic stories and learned that every story has its own way of wanting to be told. Some need a very short form, like a joke or poem, others need to be elaborated, turned into books or films. I also composed, wrote poetry, but always after developing the story first. It has to have a story.”

Born in Munich but moved to Berlin as a child of a puppeteer father and architect mother, Riemann remembers her father “telling us great bedtime stories, inventing and changing them as he told them. I learned that stories are like clay: you can shape and model them. He was my best teacher.” Her mother, “was the exact opposite, from a very scientific background. She’s always supported me in my direction, though.” Back then, Riemann lived in the “still very run down, there wasn’t even train service” district of Friedenau. “We still had wartime ruins. There were lots of academics, all without money! It’s gentrified now, of course.”

Living with hippy parents can take its toll, however, and Riemann “dropped out at thirteen! I ran away from home and squatted in Kreuzberg, in the Rauchhaus, which I think was Berlin’s first squat. I couldn’t stand my parents! Nobody could! They couldn’t stand each other! Always arguing and discussing! So off I went!” Looking back, Riemann admits “I shouldn’t have done it that early because there were a lot of experiences I could have avoided.” During a phase of living rough, Riemann started drawing and selling comic books and “I made a bit of a living too. Then, when I was seventeen, I met the comic book artist Gerhard Seyfried. He was quite famous at the time but had no idea what to do next, whereas I had so many!”

Seyfried basically ‘professionalized’ Riemann and they collaborated on two now classics of the genre; Future Subjunkies and Space Bastards. “I was seventeen when the first one came out,” Riemann explains, “and it inspired the nascent techno scene, they even named their festivals after our jokes! Somehow we hit this upcoming scene with our books, lifestyle and the main characters sort of floating through the stories,” she elaborates. “They were more ideas and feelings than stories, but they hit the zeitgeist.”

Then, aged 26, Riemann “needed money!” and teamed up with Völker Schlöndorff, as you do! “Through him I met the Babelsberg film scene,” she says, “wrote a treatment that did not work out, but then I applied for a scholarship in Munich and got accepted, where I wrote my first script, BLAME IT ON THE DOGS.” This dark comedy about a man who is afraid of dogs and falls in love with a woman who then buys herself one, was produced by ARD in 2001 and shown at the Munich Film Festival, later winning Riemann the Tankred Dorst Film Script Award. “I think it’s one of the best I’ve written,” she says proudly.

Still writing, Riemann then teamed up with producer Herbert Rimbach of Avista Film: “He wanted a script but also wanted me to direct. I was told the same thing on BLAME IT ON THE DOGS but did not believe it. But Riemann, who describes herself as “an introvert,” had made three or four shorts by then (“Just to see what it was like”) and so she agreed.

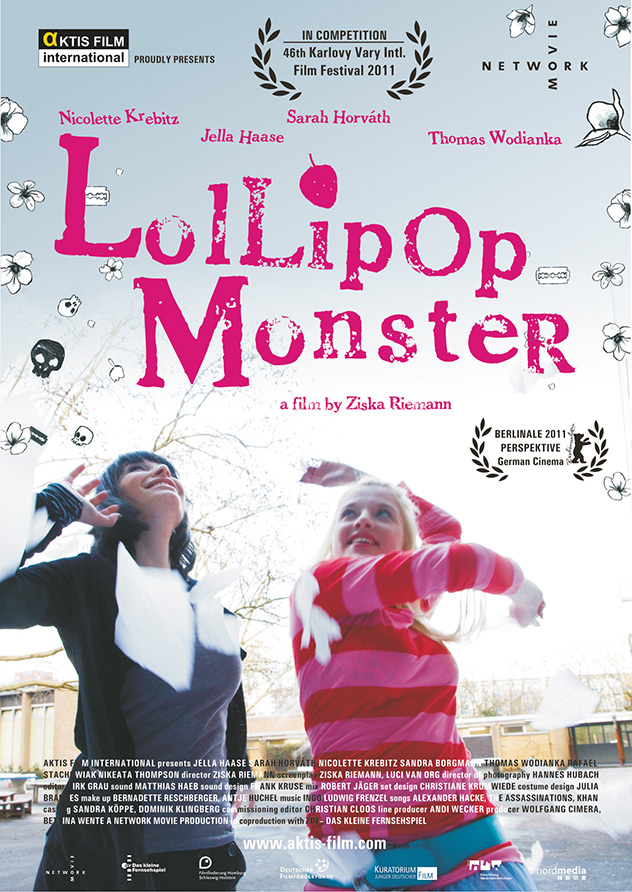

“I really enjoyed it,” Riemann says of her directorial debut, LOLLIPOP MONSTER (2011). Eventually produced by Network Movie and ZDF Das kleine Fernsehspiel, this dark, coming-of-age story, which Riemann also co-wrote with Luci van Org and has been compared to HEAVENLY CREATURES and the experimental Czech film DAISIES, “is her and my story. We met at a party when we were 20 and realized we had known each other as kids. We were terrible kids! Ringing doorbells and running away and so on. But if we had been together as teenagers we would have been monsters!”

What Riemann describes as “an intense story, an intense film,” won her regular cinematographer Hannes Hubach and lead actress Jella Haase Bavarian Film Awards. The film opened the German Film Festival at the MOMA in New York, and also screened at the Berlinale, Karlovy Vary and Golden Horse in Taiwan. Posted by eager fans on YouTube, “it was a big success, especially in the UK. We hit ten million views till it was pulled. It was rated 16 but really resonated with a younger audience.”

Riemann is currently in post-production on ELECTRIC GIRL (WT), about a young woman who dubs anime, Japanese animation, and slowly comes to believe that she herself is the lead character. “She starts to see her role as saving the planet, developing superhero powers to do so,” Riemann explains, “but in the end realizes that she is bipolar. My friend, who is the role model for the character, has the worst possible form of it. And she hates the word ‘bipolar’. She says it’s manic depression because that’s what it is: manic and depressive! I want to dedicate the film to her.”

It’s a lot to juggle: “There is much animation, many stunts, special effects, underwater shots, a great deal to coordinate, but the edit is almost done and I’m maybe finished in April.” Riemann has to be because “I’m already shooting my next one, in June, a teenage sex-comedy called GET LUCKY. It’s all about kids having it out in a house by the Baltic.”

All the now classic Riemann-signatures are going to be there: “It’s full of jokes, very light, funny, but of a punk rock style, with some animation, rough and dirty. I wrote the script, after all! I wasn’t sure about directing but the producers at Deutschfilm and Rommel Film wanted me. I think I can do something more mainstream but it still has this dirty side. I can’t change completely! And I’m working with my usual cameraman, Hannes Hubach.”

So how to describe a Ziska Riemann film? “It has very strong visuals, a lot of pop culture elements. LOLLIPOP MONSTER had music videos, ELECTRIC GIRL has animation. All my films have slightly exaggerated colors,” she explains. “Comic books involve working with a ‘Ka-Pow!’ at the end of every page to get you to turn to the next, whether it’s a strong stop or something to chew on. My films have a strong moment at the end of each scene. I’m totally more into colors, emotions, wild people, strong characters that express themselves, not quiet ones.”

“I think people who were former comic book artists become really good directors,” Riemann continues. “Like Tim Burton, Terry Gilliam, there is always a connection between comic art and film. I’m not so into Marvel but I like the supernatural in films: everything is possible, your characters can do anything.” She cites GHOST WORLD and HAPPINESS as two films that had a very strong influence on her.

A casual cinemagoer, Riemann’s dream project is The Tigress, a novella by Walter Serner, “about a woman nobody believes can be tamed. She lives in Paris, everyone calls her The Tigress. Then a young man comes, tries and fails. It has drama, humor, tragedy, because they are in love. I read it a long time ago and was so impressed. I identify with my characters, of course,” she continues, “but I think I’m pretty tamed by now! I know a lot of difficult people and I like that. I like the complicated, I like psychos; it’s always interesting! But I think I’m just a normal woman by now! I dunno! I used to be driven by neurosis, but not anymore!”

Simon Kingsley