A PORTRAIT OF DIRECTOR THOMAS STUBER

photo © Jörg SingerWE are standing in the entrance area of Starbucks in the great hall of Leipzig’s train station, directly opposite the tracks. Briefly, we look up at the old wooden, coffered ceiling and the glass skylight, through which soft, intense light falls as if in a painting by a 17th century Dutch master. We want to get a coffee, we have just under two hours for an interview, but we hesitate in face of the hot drink chain’s standardized world. Then Thomas Stuber says: “Shall we go somewhere else, to the station pub? It’s a different world, though.”

During the short walk to the pub the Leipzig-based director tells me that where the Starbucks has moved in there used to be a Mitropa restaurant. “I was there when I was still a kid, in the days of the GDR, and I ate solyanka in this incredibly high space.” Somehow, it survived the station’s redevelopment along with its side arches and the four old, 24-piece chandeliers — but only somehow. “In the old days people still used to wait in stations,” Stuber says, “today you go there to shop.”

“ … and now, a fresh draught beer!” it says on the red poster on the right beside the entrance to the bar “Gleis 8”, which must somehow have been overlooked in its stone niche during the station’s commercialization. “Open Mon. — Sun., 10 am — midnight” we read on a small cardboard sign; above that, there is a sticker indicating that smoking is definitely still permitted here. The center of the room is dominated by a square-shaped bar counter, around which there are a few small tables on high central pedestals. Bar stools as well. It’s just before midday and almost all those sitting here are men, with a lager or an ale in front of them, not the first beer of the day, I’m sure.

It is Thomas Stuber’s birthday. His 35th. I congratulate him. “It’s too early for a beer, really,” he says, but today it would be OK. But first he orders us two cappuccinos, anyway, which the barman accepts with stoicism, as he does our order of two small beers a bit later on. From an ash tray, a pillar of smoke rises straight towards the ceiling, a long worm of ash hanging on a cigarette as if a joss stick has been lit to create the right atmosphere. Gleis 8 is a pub in which Herbert might sit, the poverty-stricken boxer suffering from ALS in Thomas Stuber’s first film — of the same name — for the cinema, which was launched in Germany in March. It’s a pub exuding the demi-monde, smelling of alcohol and smoke, where men huddle: leading peripheral lives, lonely and contemplative, gazing into their glasses, or — like the old guy opposite — slumped, staring at the tracks, as though waiting for a train that will carry them away and finally deliver them from this existence.

The pub suits Thomas Stuber. There is something real, something undisguised about it. He often comes here together with his friend and screenplay author, Clemens Meyer. When they return to Leipzig from events and cinema premieres, they end up in Gleis 8, entering this transit area before heading home, just for “one more Maria” (Mariacron), as writer Meyer affectionately calls Germany’s most-sold brandy. During tricky phases in the screenplay, the two of them sit here two or three times a week sometimes, talking about films, about the piece they are currently writing, or “just chatting,“ as Stuber puts it.

Those wanting to grasp how this director who went to the Filmakademie Baden-Württemberg from 2004 to 2011 sees the world cannot get around Gleis 8. Watching life at work. Not showing the beautiful in a beautiful way but discovering the beautiful in the marginal — without turning it into kitsch or resorting to romanticizing. “I would like to be representative of cinema with great pathos and emotion, not the sort that anatomizes things,” Stuber says. “I stand for a celebration of pain, tragedy and emotion using powerful images. That’s what I want to see in our cinemas.”

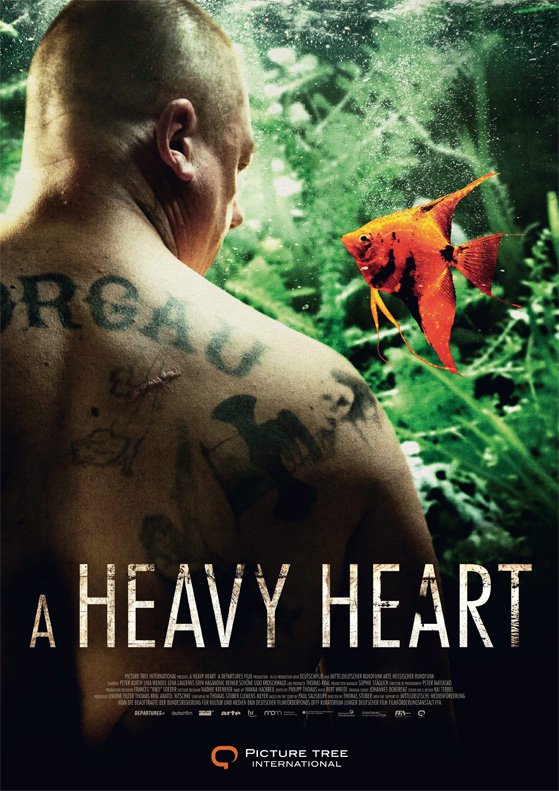

His film A HEAVY HEART (HERBERT) is a melodrama that brings us closer to a man, to all his poverty and pathos, his helplessness and hopelessness, his isolation — but does so with such tenderness that it will be a long time before we can forget this fallen boxer from Leipzig (played by Peter Kurth). At the end of the film we want to embrace him.

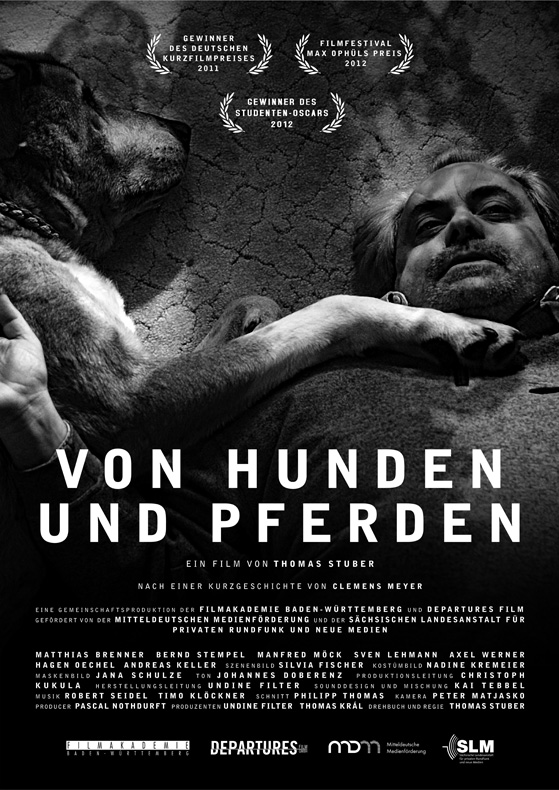

A HEAVY HEART is one of the best German feature films of recent years, but the Berlinale still didn’t want to show it, so it ran at the big North American festival in Toronto, where it was much applauded, then afterwards at the Hof International Film Festival in Upper Franconia. The critique after its cinema launch in Germany was really good. The reviews repeatedly commented that this up-and-coming director from Leipzig — who had won the student Oscar® in silver for the best foreign language short with his graduation film OF DOGS AND HORSES — recalls Rainer Werner Fassbinder and his male melodramas of the seventies.

Thomas Stuber is surprised by this, as Fassbinder was never a role model he related to: “Someone in The Hollywood Reporter invented that business with my Fassbinder style after Toronto, and then it was read and copied by a critic here. That’s how that idea was born. But Douglas Sirk is a far more important director for me. Fassbinder loved his work, too. So there is a connection. What’s brilliant for me about Sirk, somehow, is that he was in Leipzig (from 1929 to 1935 artistic director of the Altes Theater) when he was still Detlef Sierck. Then he was banned from working. He escaped to America and called himself Sirk. Just like my boxer Herbert wants to make it over there, and dreams of Chicago.”

We could probably sit in this pub opposite platform 8 for much longer. There’s a lot to talk about, like how hard it is to combine a career as a filmmaker with his desire for family life. Thomas Stuber has just become a father for the second time. About real pathos and false kitsch. About the German film-support system. About Leipzig. About the right screenplay. About actors. About dogs. About Hollywood. About the man behind the bar who doesn’t lose his stoical demeanor when Thomas Stuber orders his second beer just after one o’clock. One more is OK. After all, it is his birthday. Then my train is due to leave. We embrace each other. On the way to the platform I take another quick look into Starbucks. I‘m glad we chose the different world.

Moritz Holfelder