AND THE OSCAR GOES TO GERMANY

Stories from German Oscar history

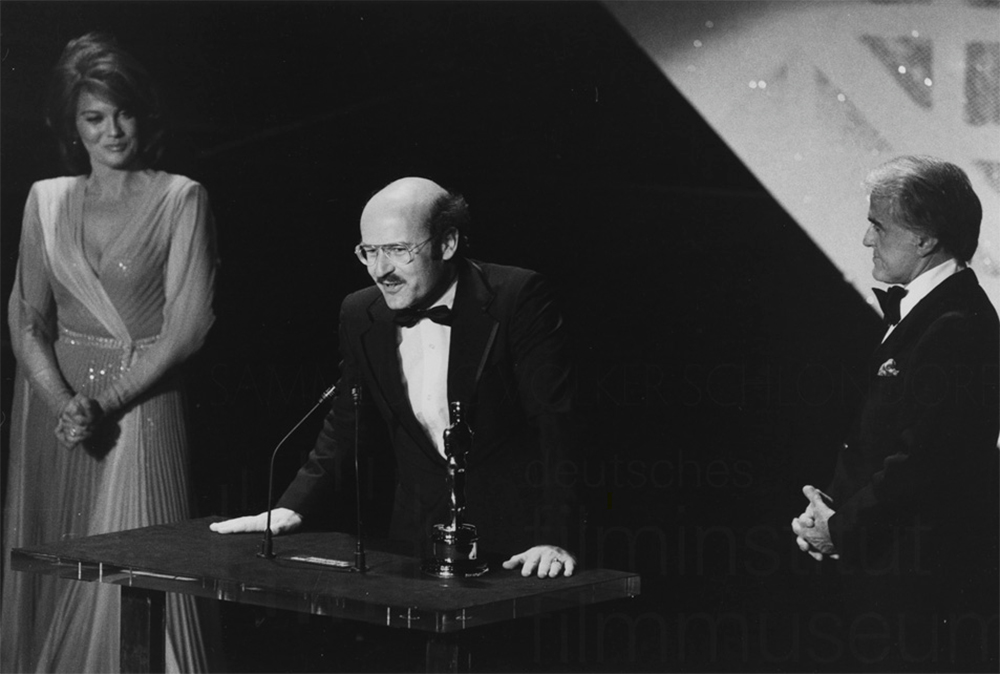

“The hero of THE TIN DRUM, you know, is named Oskar, and for all the time we were making the film we wondered what kind an omen this could be.“ With these words, Volker Schlöndorff, visibly excited, accepted the first Oscar that a German film could win in the Best Foreign Language Film category at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion on April 14, 1980. Three other German films went on to win again – and in most cases the win marked a high point and a turning point. However, THE TIN DRUM was not the very first German film to triumph in Hollywood.

Volker Schlöndorff – THE TIN DRUM © Academy Collection Archive Long Photography

But let‘s first look at how it all began, because even here the Oscar win for a German creative marked a radical turning point: On May 16, 1929, the Academy Awards took place for the very first time, on the sidelines of a dinner at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel. Emil Jannings, once pompously declared “Best Actor in the World“ by the press, was honoured as Best Actor for his roles in THE LAST COMMAND (Josef von Sternberg, 1928) and THE WAY OF ALL FLESH (Victor Fleming, 1927). But it was of little use to him. He was not even present at the ceremony but was already back in Germany.

A quite significant invention had quickly brought his promising Hollywood career to an end: the sound film. The Oscars she won in 1937 and 1938 in the Best Actress category did not bring Düsseldorf-born Luise Rainer any luck either. Dissatisfied with her roles and the studio system, the only German actress to date to win an Oscar left Hollywood in a dispute and is said to have given one of her Oscar trophies to a removal man in London. Other artists in exile later had more success with their Oscar wins, such as cameraman Karl Freund, composer Franz Wachsmann and film architect Alfred Junge, as well as a number of other German artists and technicians who won the coveted prize for individual achievements during 96 Academy Awards ceremonies.

But back to the first Oscar triumph for a German film. It was April 4, 1960: two West German directors had taken their seats in the RKO Pantages Theatre in Los Angeles and must have looked around nervously. There they sat, barely 15 years after the US authorities had systematically dismantled Goebbels’ visual propaganda machine, as two ambassadors of West German film in the midst of cinema stars such as Charlton Heston, Jack Lemmon, James Stewart, Doris Day, Audrey and Katharine Hepburn, Elizabeth Taylor and Billy Wilder, Fred Zinnemann and William Wyler. Like all these larger-than-life figures of Hollywood cinema, the two Germans were also nominated for the Oscar, whose 32nd award ceremony was intended to honour the achievements of 1959. Both of their films were great cinema successes, in Germany as well as around the world, and yet the international representation of German film on this Monday could not have been more different.

Bernhard Wicki’s anti-war film THE BRIDGE (1959) was nominated in the Best Foreign Language Film category. After West German film of the 1950s had previously approached the Second World War primarily through portraits of officers active in the resistance or through the increasing glorification of soldiership as a related statement on the rearmament of the Federal Republic of Germany, Bernhard Wicki’s feature film THE BRIDGE turned not only against National Socialism, but also fundamentally against the insanity of war and militarization.

Bernard Grzimek – SERENGETI SHALL NOT DIE © Academy Collection Archive Long Photography

The second German who was eagerly awaiting the award ceremony that evening at the RKO Pantages was Professor Bernhard Grzimek, veterinarian, behavioural scientist and passionate wildlife filmmaker. The then director of Frankfurt Zoo and author of the standard work “Handbuch der Geflügelkrankheiten“ (“Handbook of Poultry Diseases“) was nominated for an Oscar in the Best Documentary Film category with SERENGETI SHALL NOT DIE, a film that not only presented previously unseen spectacular images of the natural preserve, but also took a clear eco-political and moral stand

Even back then, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences was in favour of political and ecological commitment and actually awarded the Oscar for Best Documentary Film to the German wildlife filmmaker. Bernhard Wicki’s THE BRIDGE, on the other hand, did not make it, losing out to ORFEU NEGRO (1959) by Marcel Camus. Bernhard Grzimek dedicated the Oscar to his son Michael, who died in a plane crash during the making of the film. Who Grzimek did not mention and who is often forgotten to this day when it comes to the making of SERENGETI SHALL NOT DIE is the editor Klaus Dudenhöfer. It was he who distilled the stories from the footage, which was mostly shot without a concept, and assembled them into the entertaining film that is still enjoyed today. With Helmut Käutner’s THE CAPTAIN FROM KOEPENICK, a film edited by Dudenhöfer had already been nominated for an Oscar three years earlier – until his death, he regretted not having held Grzimek’s statue in his hands at least once.

Bernhard Grzimek’s triumph at the Oscars was highly symbolic for German film. After all, there had already been nominations for West Germany in the Best Foreign Language Film category after 1945 before that: in 1957 for THE CAPTAIN FROM KOEPENICK, in 1958 for THE DEVIL STRIKES AT NIGHT by Robert Siodmak and for Franz-Peter Wirth’s ARMS AND THE MAN in 1959. However, there had been nothing to win for German feature films up to that point, and even less after 1960, as West German cinema fell into a serious crisis and only got back on its feet artistically with the auteur film. Grzimek’s award can therefore also be read as a tribute to the strong German film market in the 1950s, which was not only able to assert itself nationally with dream market shares, but was also able to achieve international recognition.

It is therefore fitting that it was only exactly twenty years after Bernhard Grzimek that another German film was honoured with an Oscar, and with it an entire wave, so to speak. Volker Schlöndorff’s Oscar triumph in 1980 marked the high point of a creative phase that continues to have an impact today. His success symbolically crowned the international recognition of the auteur film generation that had produced the New German Cinema at the end of the 1960s and was now beginning to get caught up in the self-created confusion of the new film funding and a somehow enigmatic lack of narrative content.

In his acceptance speech in Hollywood, Schlöndorff dedicated the award to his “fellow directors over there“ and placed them and himself in the tradition of Lang, Wilder, Lubitsch, Murnau and Pabst: “You know them all, you welcomed them.“ However, the success of THE TIN DRUM had little impact on German film at the time. Even Schlöndorff turned his back on German structures for the time being and shot internationally with Dustin Hoffman, Richard Widmark, Alain Delon and Faye Dunaway.

Filmstill BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB by Wim Wenders © ARTHAUS

Wim Wenders took a similar path, increasingly shooting internationally, and has today earned himself an indisputable place in the pantheon of international cinematography. Four of his films, all financed internationally to varying degrees, have been nominated for an Oscar to date: the three films BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB (2000, US-German co-production), PINA (2012, German-French co-production) and THE SALT OF THE EARTH (2015, French-Italian-Brazilian co-production) in the Best Documentary category and the Japanese production PERFECT DAYS (2024) in the Best Foreign Language Film category.

This makes Wim Wenders the German director with the most Oscar nominations. However, the German filmmaker with the most nominations of all works in a different department: it is film composer Hans Zimmer, who has been nominated twelve times and won twice.

Filmstill NOWHERE IN AFRICA by Caroline Link © Zeitgeistfilm Archiv

Talking about individual achievements at the Oscars: Editor Patricia Rommel has successfully edited four of the 21 German films that have been nominated in the Best Foreign Language Film category to date. Two of these films went on to win: NOWHERE IN AFRICA (2003) and THE LIVES OF OTHERS (2007). Roughly twenty years after THE TIN DRUM, she exemplifies the next remarkable resurgence of German cinema, which was significantly recognised both domestically and internationally. Following the reunification of Germany, measures to improve training opportunities and the ever-increasing financial resources of funding institutions led to a significant qualitative and quantitative upswing in German film from the mid-1990s onwards.

German cinema produced countless talents whose influence reached as far as Hollywood. Since 1998, this has not only been reflected in ten nominations and two wins in the Best Foreign Language Film category (renamed Best International Feature Film in 2021), but also in two victories in the Best Short Film categories. What is particularly noteworthy, however, are the 28 Student Academy Awards won by German talents since 1998, including filmmakers such as Florian Gallenberger, Ulrike Grote, and İlker Çatak, the latter of whom was later nominated for the Academy Awards with THE TEACHERS’ LOUNGE.

Oscars for ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT © AP-John Locher

The absolute pinnacle of this development is Edward Berger’s ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT, with its nine nominations and four wins – a record likely to stand the test of time. Only time will tell whether this victory marks yet another turning point for German cinema – from a film policy perspective, at least, it certainly seems to be on the horizon.

Oliver Baumgarten