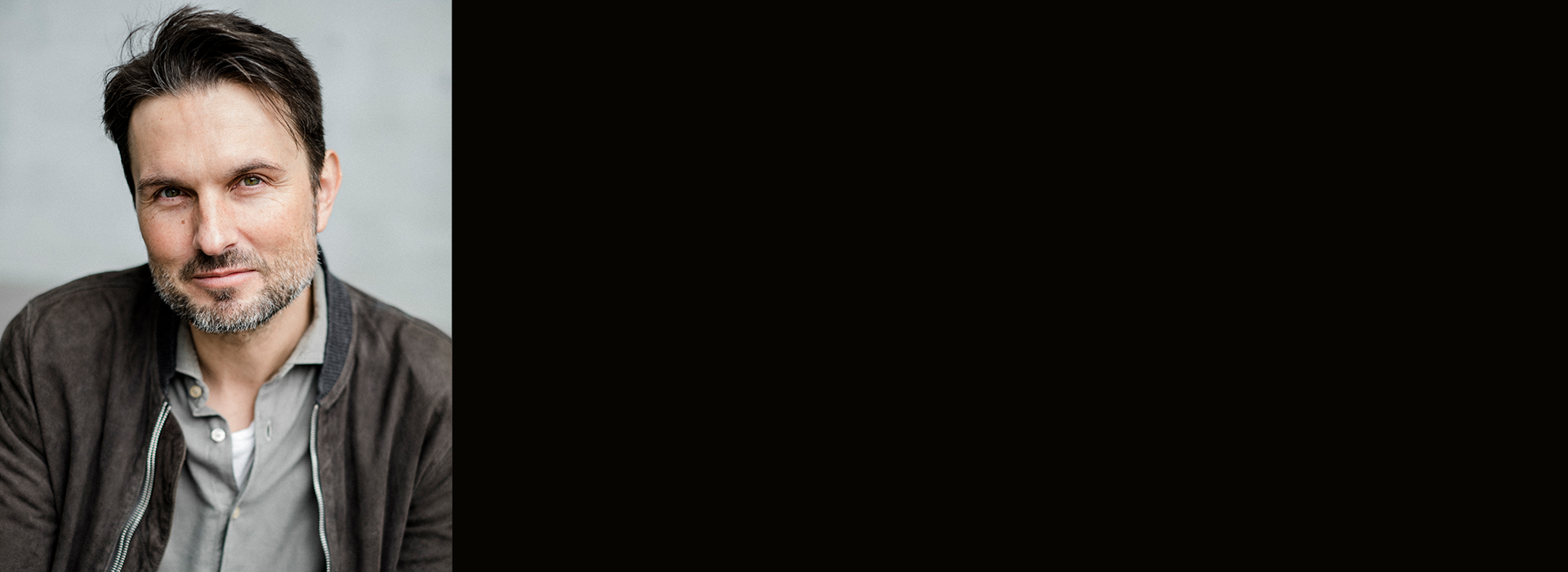

A PORTRAIT OF DIRECTOR SIMON VERHOEVEN

Simon Verhoeven © Sarah Domandl“Of course, it sounds good when you put it like that.” Simon Verhoeven has to laugh when asked right at the beginning of our telephone interview what it actually feels like to be one of Germany’s most successful directors. He himself would never put it that way, of course, but the figures speak for themselves: four of his last five movies reached well over a million admissions in Germany. Most recently, his comedy NIGHTLIFE starring Elyas M’Barek and Frederick Lau not only topped the charts straight after its release in mid-February until cinemas were closed due to Corona, but also immediately after their re-opening in June. “However, that’s not decisive for my well-being as a director,” the 48-year-old adds quickly. “The success that makes me happy today is that I am given the freedom to realize my projects the way I envision them. I know from my own experience that it’s not a matter of course in this profession, so I am grateful for that.”

Verhoeven prefers to leave the analysis of why his films are so well received by the public to others. But he does note some similarities between the love affairs and everyday worries of different guys in the romantic comedy MEN IN THE CITY (2009) and its sequel MEN IN THE CITY II (2011), the charming, politically charged satire WELCOME TO GERMANY (2016), nominated for the German Film Award, about a family that takes in a fugitive, and the turbulent buddy and date trip through Berlin’s nightlife scene in NIGHTLIFE: “A very warm and affectionate view of my protagonists and the trials and tribulations of life runs like a thread through my work,” he says. “Even when the tone becomes wicked or satirical, my characters are always visible as people. If you like to put it that way, maybe this is the secret of my success. People expect a funny comedy, but in the end they are much more involved emotionally than they had expected. Because there’s always a seriousness to the story, as well.”

Cinema as a highbrow affair was never Verhoeven’s thing, not even during his childhood. Born in Munich, he grew up not only as the son of actress Senta Berger and filmmaker Michael Verhoeven, but also as a passionate film fan: “On Sundays, many people went to church in our Catholic village – but we went to the cinema. When the lights went out and the fanfares of the big film studios could be heard, it was almost a religious experience for me.” The movies of Charlie Chaplin were the first that he went to see regularly with his father, later joined by those of Billy Wilder and Steven Spielberg, but he also regards the works of Helmut Dietl or Loriot as formative. Great entertainment for a big audience was his goal from early on, always following the motto: “A film needs to touch and move me, make me laugh or cry. If it’s all about getting the message across, I think that’s awful.”

The fact that Verhoeven ended up in the USA after graduating from high school was due less to the influence of American cinema and more to the distance: “My heart had been thoroughly broken and I just wanted to leave. Besides, no one in America knew my parents, so I could simply be a student. A real liberation.” He studied acting in New York and film music in Boston, and later bagged one of the coveted film directing places at the prestigious Tisch School of Arts at NYU. “If a professor there praised a film of mine, I knew it was because of me alone. That was incredibly encouraging.”

After his first feature film 100 PRO (2000), Verhoeven earned his living as an actor for a while. “It was only a means to an end because some directing projects crashed. But I learned an enormous amount about how to handle actors,” he remembers, and seems to be quite good at seeing the positive in experiences that could have been better. For example, he calls the horror film UNFRIEND (2015), his first English-language work, “a creative disappointment”, but goes on to say: “With the means we had at our disposal, it turned into a visually beautiful nightmare trip, which can definitely hold its head up among Hollywood productions – and has been sold all over the world.”

Verhoeven has no doubt that his method of cinematic narration can also work beyond Germany. He has used the past few weeks to write, to work on a project that he “couldn’t imagine being more exciting.” He is not yet allowed to reveal much, only that it is a German story but with an international orientation. “The idea of producing films from Germany that can be seen not only at three or four festivals, but really reach an international audience, is still a great desire of mine, and a real motivation,” he says in farewell – and you can almost hear the anticipation in his voice. Well, if that’s not success!

Patrick Heidmann