A PORTRAIT OF DIRECTOR KARIN JURSCHICK

Karin Jurschick (© HFF München/Robert Pupeter)“For me, making documentaries means immersing myself in an experience. Of course planning is necessary, but during the work process I hand over control and open up to what is and whatever I can perceive. Even if that throws my previous opinions overboard and leaves me with more questions than answers.”

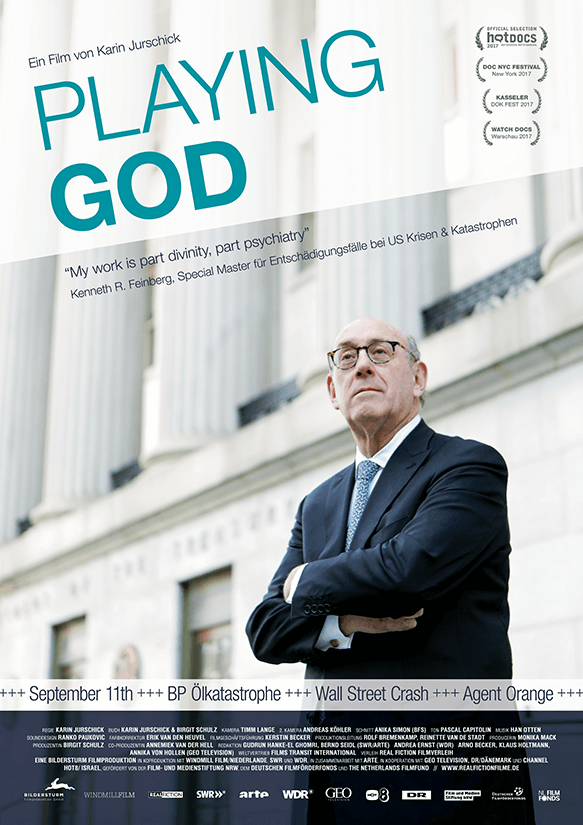

This is an attitude with which director Karin Jurschick also confronts current developments in the genre, which are focusing increasingly on the formatted. Her most recent work conveys this open approach in a practical way. PLAYING GOD portrays US star lawyer Ken Feinberg, who is commissioned by the government to determine compensation for victims of the 9/11 attack or the Deepwater Horizon explosion, for example, and shows the often apparently cynical outcome of his work. Here, Jurschick balances brilliantly between rejection and sympathy, attention for the contradictory person himself and insight into his integration into a tight web of legal and economic guidelines. It is a highly political film, which premiered at Hot Docs in Toronto in 2017.

Recently, Jurschick also presented it at the ENCOUNTERS Documentary Film Festival in Cape Town and reported how surprised she was that South African audiences were also able to get so much from her film. One reason is that questions of compensation are also very relevant there at the moment. “It was nice that the different sides of my protagonist were also seen so clearly there, as well. In the USA that was much more difficult: there, it’s obviously confusing for someone to be a good guy and a bad guy simultaneously.“ Perhaps this was also one reason why an attempt to involve the US broadcasting station PBS in the production failed. But primarily, Jurschick believes, that was probably fear of domestic audiences rejecting the idea of a German telling them anything about America.

Jurschick’s film career also began by approaching a man with a very special character: the director’s father, with whom she had broken off contact after her mother’s early suicide. Born in Essen in 1959, she studied film and media studies and then made a name for herself as a journalist and co- founder of the first and largest German women’s film festival, the Feminale in Cologne, especially in the feminist film scene. But at some point, the past developed into too big an issue. And at the age of 40, Jurschick returned to her old apartment, where her 91-year-old father was still living. She had brought along many questions – and a camera as a means of approach and distancing at the same time.

This emotionally intense work with her father was also good schooling for later work with difficult protagonists. It resulted in a film (DANACH HÄTTE ES SCHÖN SEIN MÜSSEN) with a sober precision that provides a counterpart to the intra-family self-reflections popular today. This was also due to Jurschick’s attention to historical contexts: “My father was born into the First World War,” she says, “my mother into National Socialism and the Second World War. For me, what I had experienced at home, which ended with my mother’s suicide, was always connected to the ‘big (hi)story’. I had the feeling I was experiencing an invisible war that had strayed into our private life, strongly influenced by the wars they had experienced.”

She made this clear in the film using a complex montage technique and a reflectively distanced style, which also condenses private history into an analytical view of German post-war society. At the premiere of the film at the International Forum during the Berlinale 2001, audiences and critics were electrified, and many other festivals and prizes were to follow. And suddenly Jurschick had become a celebrated “filmmaker” due to her unexpected success.

It presented an opportunity and a challenge at the same time. Jurschick went on to deal with wars, crises and (above all sexualized) violence later: the vicious circle of prostitution and trafficking in women that international aid organizations had helped to trigger during the Balkan wars (THE PEACEKEEPERS AND THE WOMEN, 2005), the consequences of Chernobyl (THE CLOUD, 2011), or the complex of drones, AI and hi-tech warfare (WAR AND GAMES, 2016). “I am driven by the desire to find a visual form for something that doesn’t produce a clear image, something that is complex and painful. In terms of content, my interest has always focused on systemic questions,” she says in respect to the source of her creative energy. And obstacles?

On the one hand, “documentary films that do not follow classic dramaturgy involving a hero’s journey but aim instead at recognition and questioning, are rarely accepted by festivals today.” Another urgent task for filmmakers worldwide are the new “toys and technologies” that are driving them forward at a continually increasing pace. For two years, Karin Jurschick has also faced a new responsibility as a professor at the University of Television and Film in Munich, which she describes as “fulfilling in every sense.” Slowly, however, she is beginning to feel the “desire and strength” to conceive a new project of her own. Those of us who are not students are glad to hear it.

Silvia Hallensleben