A PORTRAIT OF DIRECTOR LARS KRAUME

photo © Wolfgang SchmidtIT was his father’s fault: “He’s a cineast and he dragged me to the cinema to see all sorts of films very early on,” Lars Kraume recalls. “As a youngster, I was particularly impressed by the films of the Italian neo-realists, and most of all by ROCCO AND HIS BROTHERS.”

Kraume was born near Turin/Italy in 1973. Growing up in Hesse, not far from Frankfurt, he soon developed a huge passion for pictures himself — he began to take photos at 12, and at only 15 he borrowed the triple-lens Bolex movie camera belonging to his father, a commercial graphic designer: “Slowly but surely, the bold idea emerged that I could perhaps make films, too.”

While still at secondary school and after his graduation — while completing his alternative to military service — he worked as an assistant to well-known photographers; after his successful application to the German Film and Television Academy (DFFB) in Berlin he moved to the capital in 1994, where he still lives today. He openly admits that he lacked confidence at the start of his course in direction. But Kraume tells me that Florian Lukas, already an experienced actor even then, with whom he made two prize-winning short films at the DFFB, gave him back his self-confidence: “Florian said that working with me was immense fun, so I thought maybe I wasn’t entirely out of place as a director!”

Kraume certainly demands a lot from his actors: “I expect them to do much more than obediently recite the words in the script; they need to incorporate their own views and experience of life as well. Working with me, actors can play an active part in conceiving their roles — I am always open to suggestions.”

Kraume took this freedom to extremes in his semi-documentary road movie NO SONGS OF LOVE, for which the protagonists developed their own characters without a script, improvising most of the dialogues: “I wanted to break through the scenes’ surfaces so that the actors were no longer acting but being.”

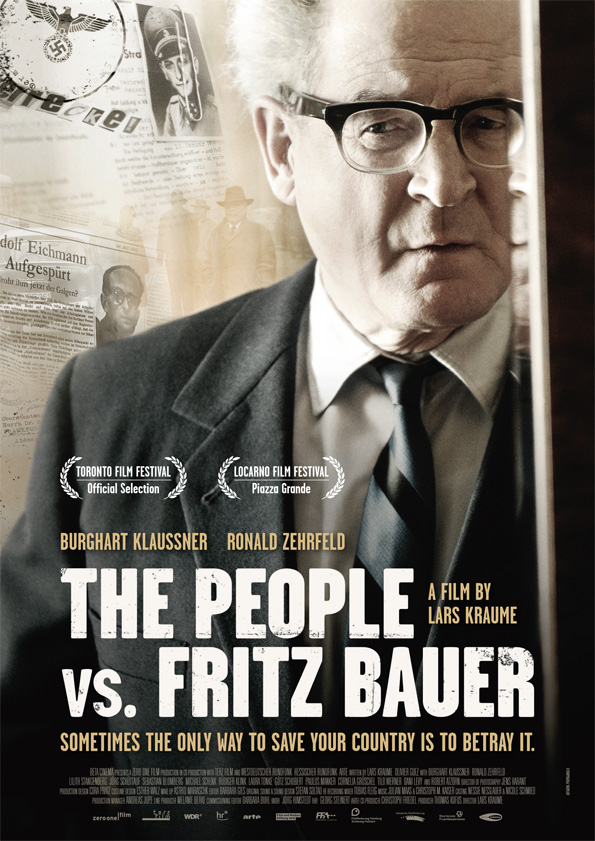

Kraume is seen as rather a chameleon because he won’t be pinned down to a single genre or style. In his graduation film at the DFFB, DUNCKEL, which was awarded the Adolf Grimme Prize, he had worked through three completely different facets already: an unusual crime story, it comprises three episodes telling the stories of three very different brothers after a failed bank robbery. Since then, the flexible director has made, among other things, a lively satire on commercialism (VIKTOR VOGEL — COMMERCIAL MAN), an apocalyptic vision of the future (DAYS TO COME), a cheerful drama about death (MY SISTERS), and an atmospherically haunting political thriller (THE PEOPLE VS. FRITZ BAUER).

“The reason why my films are so different is that I try to embark on the biggest possible adventure each time,” Kraume explains. “My most important role models have always been directors capable of changing, such as John Huston, where you always have the feeling that every film is a new and exciting venture. I’m sure I wouldn’t be capable of constantly repeating myself. If there were no new challenges for me, I could never summon the energy to engage with a subject so intensely as a filmmaker.”

Nevertheless, there is something like a thread running through his work: family constellations often play a decisive part. “The relationships between siblings, the family as a place of retreat and a battlefield — that is all close to my heart,” Kraume explains. “I myself come from a large middle-class family, in which there is still a strong sense of solidarity but also a lot of potential for conflict. It’s interesting that films about bourgeois families have a much stronger tradition in France than in my country, where the subject of the family is dealt with largely in social dramas set in a very different milieu. Middle-class family circles like those I depict in my films seem to be frowned upon in German cinema — obviously they are regarded with social envy, although Germany is actually a very prosperous country.”

A second constant in Kraume’s œuvre is his debate with political subjects: “I make films because I am worried about what’s happening in my country and our cultural sphere.” His multiple prize-winning school drama, GOOD MORNING, MR. GROTHE, was made in response to a letter published in March 2006, in which the teachers at a Berlin school admitted in despair that they could no longer cope with the escalating violence among their pupils. In his powerfully visual dystopia DAYS TO COME, among other things Kraume examined the conflict between poor and rich resulting from the uneven distribution of wealth. This apocalyptic drama filmed in 2009, in which Central Europe tries to protect itself from immigrants behind high walls, like a fortress, is regarded as visionary in face of the refugee crisis today – but the filmmaker believes the problem became virulent long ago: “Key scientists already warned us many years ago that the greatest threat to world-wide security in the future would be the flow of migrants.”

There is also a political impetus behind Kraume’s most successful film to date, THE PEOPLE VS. FRITZ BAUER. It is about a state public prosecutor from Hesse, who struggled against staunch opposition to track down Nazi criminals and take them to court at the end of the 50s. “Fritz Bauer was a true hero — one of the few there were in Germany,” Kraume affirms, “and as the title already indicates, the film is a David-and-Goliath story: the archaic struggle of an outsider against an overly powerful system.” The exciting political drama celebrated its world premiere at the festival in Locarno, where it also won the sought-after audience award.

The director underlines how important it was to him to avoid the aura of tedious school lessons and to make an exciting film with a timeless message instead. That is why he was also delighted after the invitation to Locarno, as he had very much wanted the world premiere of this specifically German story to take place abroad: “We made this film for an international audience, because I believe that Fritz Bauer can inspire people all over the world. His courage and his stubborn determination are a wonderful encouragement to everyone who is taking a stand against injustice.”

And so Kraume is very happy that THE PEOPLE VS. FRITZ BAUER has been sold in more than 20 countries in the meantime, including the USA, France, Argentina and Japan. “I think it’s a shame that usually German films are only successful abroad when they engage with German history,” he says. “But I certainly won’t let that limit me to history films!” So, onward to new challenges? “Yes,” says Kraume, laughing. “I’m already wondering what stories I could film in English.”

He still has one unfulfilled dream: “One day, I would love to make a film that appeals to a really big audience,” he confesses. “My aim is to entertain people in an intelligent way.” That sort of thing is rare in Germany, he notes: on the one hand there is banal mass entertainment, on the other some rather cumbersome niche cinema, which often seems to indulge in navel-gazing. Kraume regrets the fact that some German intellectuals turn their nose up at filmmakers who aim to reach as many viewers as possible. “Because surely that is cinema’s very own, initial strength: the fact that it enables us to experience strong emotions together, in a big group!”

Marco Schmidt