A PORTRAIT OF DIRECTOR BURHAN QURBANI

Burhan Qurbani (© Joachim Gern for the FACE TO FACE WITH GERMAN FILMS 2018 campaign)He himself would never put it that way, of course, but seen from the outside there can be no doubt: Burhan Qurbani is a real exception among German filmmakers. However, this has astonishingly little to do with the family background of the director, who appears extremely modest and thoughtful during our conversation in his shared home in Berlin-Neukölln. His parents came to Germany from Afghanistan not long before his birth, and there is no question that this also distinguishes the 37-year-old from many of his colleagues.

But there are other reasons why Qurbani and his films are unique in this country. Even the way in which Qurbani began his career can hardly be described as typical. Actually, as a youth he dreamed of hiding his nose in books rather than behind a camera; his professional ambition was to become a theater dramaturg or a literary scholar. But then he read some information material from the Filmakademie Baden-Württemberg and thought it might also appeal to him; after his school graduation, therefore, Qurbani spontaneously decided to apply.

“Unlike most of my fellow students, I had no film experience. For the whole of the first year of study I was actually busy learning the basics,” he remembers of his initial months studying the subject of Scenic Direction. “The only thing I found quite easy thanks to my practical experience in the theater was dealing with the actors.”

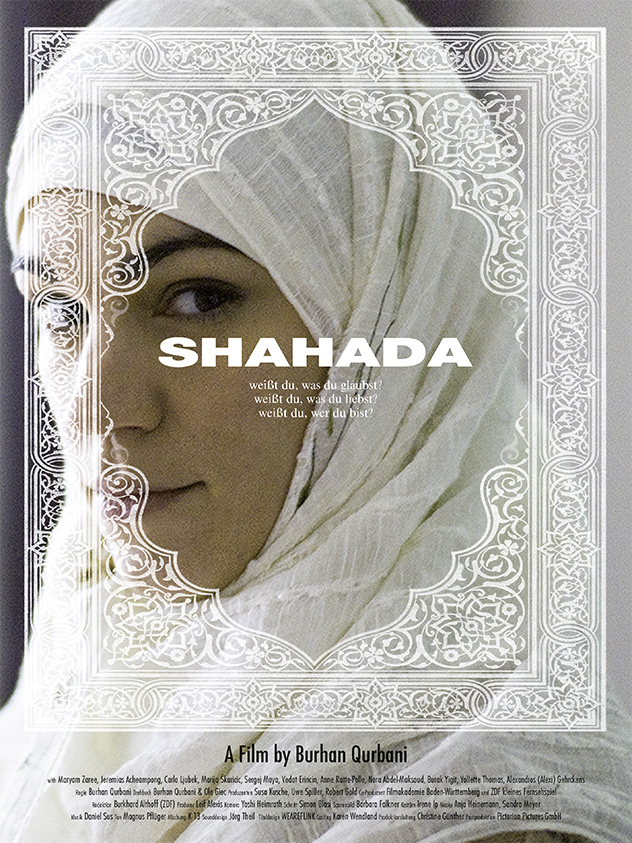

Eight years and several short films later (including some that won prizes in Hamburg, Dresden and Abu Dhabi), the end of his studies also turned out more than ordinary. Qurbani’s graduation film SHAHADA was made in cooperation with the department Das kleines Fernsehspiel at public broadcaster ZDF, but the film with its episodic narrative actually landed at the 2010 Berlinale rather than on TV. More precisely – it went straight into the competition. “So actually, you have just made a student film that’s supposed to be shown on TV sometime around 11 pm. But instead you are suddenly hauled in front of a world audience,” Qurbani recalls the rather overwhelming experience, from which, in his own words, it took him a full year to recover properly. “All at once, slowly feeling my way into dealing with criticism and the public was no longer possible. I was standing there naked, so to speak, and vulnerable. But I wouldn’t want to change it for anything. If nothing else, because the attention the film drew enabled me to travel all around the world.”

Five years later Qurbani saw his second film on the cinema screens: WE ARE YOUNG. WE ARE STRONG., which was nominated for the German Film Award for Best Film and won the Bavarian Film Prize in the category Screenplay. But it is not so much these astonishing success stories that make his works into remarkable phenomena – it is their subjects. SHAHADA presents a very modern, enlightened debate about Islam in Germany, and WE ARE YOUNG. WE ARE STRONG. re-assesses the radical right-wing riots in Rostock-Lichtenhagen in 1992, which appeared disturbingly up-to-date when the Pegida demonstrations reached their first climax parallel to the film’s cinema launch. Very few directors in this country can claim to have a finger on the pulse of German society in the same way he does.

Qurbani is correspondingly happy to accept the label “political filmmaker”: “That doesn’t mean that everything you make is automatically political. But if you introduce something into the public domain it becomes a political issue. Once something has a certain size of audience, after all, it is no longer private. Then you also take on responsibility.”

And for him, this sense of responsibility also means that he is compelled to relate something about life in the here and now, about the state of the world. “As filmmakers in Germany we get so much public money, and personally I think it’s foolish to stick to the small world of private affairs,” he says to explain his choice of themes. “Of course it’s also important to talk about love, sex and tenderness. But in the process you can open the doors and latch onto something more universal. I think we, as directors, should open and expand our perspectives.”

And so it is no wonder that ultimately, Qurbani prefers to see himself as a European rather than a German filmmaker. “I have already had chances to work in Israel and together with colleagues from France, America, Arabia or Spain. Often, I find what they are producing more exciting to watch than a lot of what I see in this country. In Europe in particular, the neighboring countries represent assets we ought to exploit,” he notes. “Of course, it should be permissible to tell German and also very personal stories. But you also need to present a broader framework, enabling people to decipher them beyond cultural borders.”

He aims to do that very thing once again with his new project. The shooting of ALEXANDERPLATZ is due to begin this spring: it is an adaptation of Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz, the screenplay written together with Martin Behnke, who was also co-author of WE ARE YOUNG. WE ARE STRONG.. Qurbani has been working on this film for a good four years now, not only at home at the kitchen table in his shared apartment, but also under the guidance of Romanian screenplay author Razvan Radulescu (MOTHER & SON) in the acclaimed Torino FilmLab, and in Los Angeles, where he was a Villa Aurora fellow in 2016. Meanwhile, the funding and casting are all wrapped up.

In ALEXANDERPLATZ the Berlin-based petty criminal Franz Biberkopf is cast as Francis, a refugee from Africa. “I want to tell a story that not only focuses on the community of sub-Saharan migrants in Berlin but also compels German audiences to really look hard at the issues,” Qurbani comments regarding the relevance of his next film. “The usual kind of refugee story probably only addresses viewers who are already interested in the topic anyway. But if you take one of the most important novels of German literary history and turn the main character into a refugee from Africa, I hope that it will be noticed in a very different way, and taken seriously.”

Patrick Heidmann